Wounded

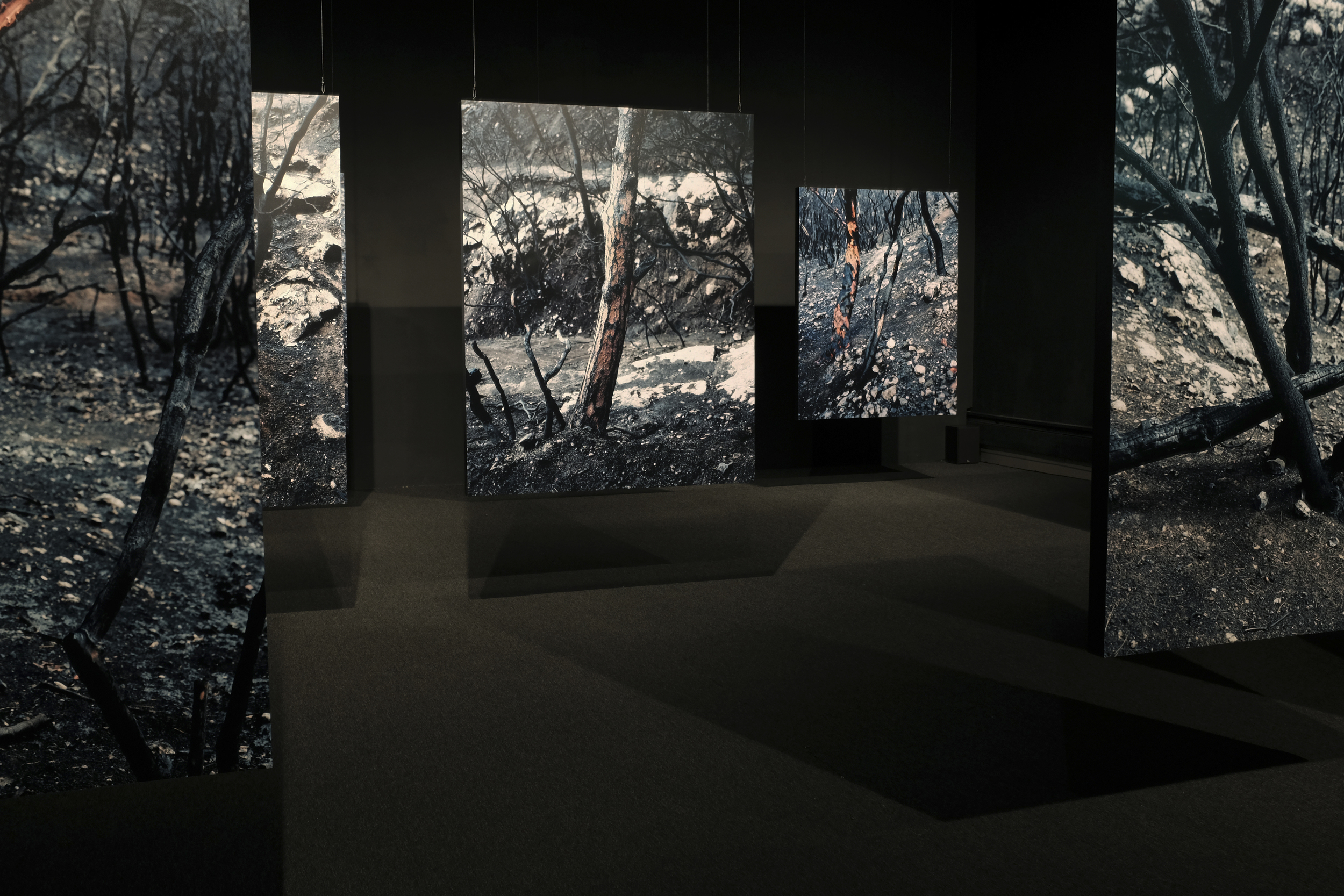

Room installation of nine 110cm x 137cm c-type photographs, with looped surround sound

Corinne Silva arrived in Palestine/Israel two weeks after a devastating fire had ripped through Israel’s Mount Carmel Forest. She travelled north towards the border with Lebanon to see for herself. Lasting four days and nights, the fire had destroyed 50 square kilometres of woodland. The day she arrived it was raining heavily. She sat in the car for several hours, then returned the next day with her field camera.

Since the declaration of Statehood in 1948, Israel has re-shaped the historic Palestinian landscape by planting over 200 million trees. The Mount Carmel Forest, a mix of oak, cypress and Aleppo Pine, was established as part of the State’s vision to ‘make the desert bloom’. Now only the charred remains of tree limbs, shining after the rainstorm, remained. I photographed them frontally at body height, without horizon line, up close and claustrophobic.

In religious texts, trees often appear in the landscape as metaphors for people and their nation. Images of trees being uprooted, withering in drought or being burned might be used to convey God’s displeasure. Across Israel there was a palpable sense of loss – the destruction of the forest a wound in the national psyche.

Wounded is an installation of nine photographs with sound. Suspended from the ceiling intermittently throughout the gallery space, the photographs allow for a wandering between them. Hung at human height, there is no choice but to confront the charred remains of the trees with one’s own body – creating a dialogue with these arborial bodies, mute victims of grief and pain, in this geographical region of ongoing trauma.

Silva’s is not the ‘monumental’ landscape photography usually made with a large format camera, the disinterested gaze offering sweeping vistas from an elevated point. Instead, this work combines photography and sound to create a multi-sensory experience of being within landscape, with an understanding that the human body – hers / the viewer’s – are inextricably part of that landscape, and therefore implicated in what occurs there.

While the forest can be seen from the front as the viewer winds their way through the suspended works, there is nothing to greet them on any return journey except a dense blackness, a void. The human-planted forest can be understood as a carpeting over of land – the backs of these rectangular objects a reminder of the illusion of this human-created ecosystem.

If the photographs lead the viewer in one direction, the sound pulls them in another. Two years after her initial visit, Silva returned to the forest. Although she had initially encountered scientists running tests on the soil, no trees had been replanted. The forest had been left to languish or recover. To her surprise she found herself wading through foliage of all kinds. The densely planted Aleppo Pine, a fast growing and popular tree for afforestation projects, had previously shed its needles thickly over the ground, choking any other flora that would naturally coexist. Now this flora had a chance to breathe.

Silva made a sound recording as she walked, scrambled, tripped over this lush, chest-height greenery. In the installation, floor-level speakers positioned in the four corners of the room project the sound of her footsteps on the soft forest floor, her body pushing its way through the foliage.

Listen to a sound excerpt:

Wounded room installation of photographs and surround sound, shown as part of solo exhibition Garden State, Ffotogallery, Wales, and The Mosaic Rooms, London, 2015